On This Date In History

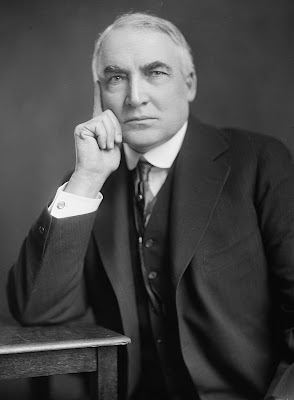

On January 10, 1923, four years after the end of World War I, President Warren G. Harding orders U.S. occupation troops stationed in Germany to return home.

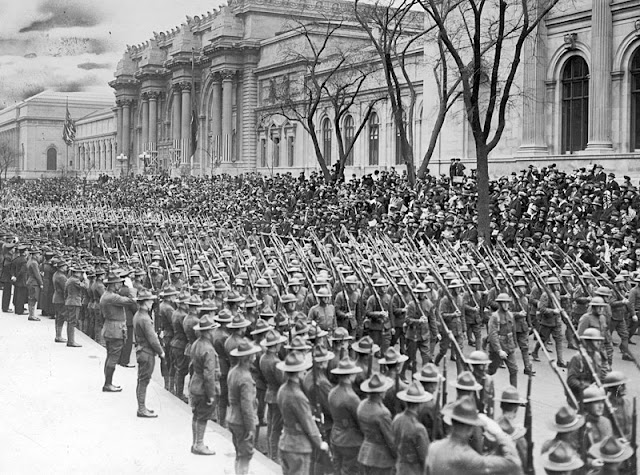

In 1917, after several years of bloody stalemate along the Western Front, the entrance of America’s fresh, well-supplied forces into the Great War, a decision announced by President Woodrow Wilson in April and provoked largely by Germany’s blatant attacks on American ships at sea, proved to be a major turning point in the conflict. American naval forces arrived in Britain on April 9, only three days after the formal declaration of war. On June 13, the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), commanded by the celebrated General John J. Pershing, reached the shores of France.

By the time the war ended in November 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe and more than 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The last combat divisions left France in September 1919, though a small number of men stayed behind to supervise the identification and burial of their compatriots in military cemeteries. An American occupation force of 16,000 men was sent to Germany, to be based in the town of Coblenz, as part of the post-war Allied presence on the Rhine that had been determined by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

In 1923, after four years in Germany, the occupation troops were ordered home after President Harding succeeded Wilson in 1921 and announced a desire to return to normalcy after the disruptions of wartime. Meanwhile, the bitterness of the German population, demoralized by defeat and what they saw as the unfairly harsh terms of peace, of which the American occupation was a part, grew ever stronger.

In 1914, a political assassination in Sarajevo set off a chain of events that led to the outbreak of the most costly war ever fought to that date. As more and more young men were sent down into the trenches, influential voices in the United States and Britain began calling for the establishment of a permanent international body to maintain peace in the postwar world. President Woodrow Wilson became a vocal advocate of this concept, and in 1918 he included a sketch of the international body in his 14-point proposal to end the war.

In November 1918, the Central Powers agreed to an armistice to halt the killing in World War I. Two months later, the Allies met with conquered Germany and Austria-Hungary at Versailles to hammer out formal peace terms. President Wilson urged a just and lasting peace, but England and France disagreed, forcing harsh war reparations on their former enemies. The League of Nations was approved, however, and in the summer of 1919 Wilson presented the Treaty of Versailles and the Covenant of the League of Nations to the U.S. Senate for ratification.

Wilson suffered a severe stroke in the fall of that year, which prevented him from reaching a compromise with those in Congress who thought the treaties reduced U.S. authority. In November, the Senate declined to ratify both. The League of Nations proceeded without the United States, holding its first meeting in Geneva on November 15, 1920.

During the 1920s, the League, with its headquarters in Geneva, incorporated new members and successfully mediated minor international disputes but was often disregarded by the major powers. The League’s authority, however, was not seriously challenged until the early 1930s, when a series of events exposed it as ineffectual. Japan simply quit the organization after its invasion of China was condemned, and the League was likewise powerless to prevent the rearmament of Germany and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. The declaration of World War II was not even referred to by the then-virtually defunct League.

In 1946, the League of Nations was officially dissolved with the establishment of the United Nations. The United Nations was modeled after the former but with increased international support and extensive machinery to help the new body avoid repeating the League’s failures.

No comments:

Post a Comment