On This Date In History

On February 4, 1789, George

Washington, the commander of the Continental Army during the

Revolutionary War, is unanimously elected the first president of the

United States by all 69 presidential electors who cast their votes. John

Adams of Massachusetts, who received 34 votes, was elected vice

president. The electors, who represented 10 of the 11 states that had

ratified the U.S. Constitution, were chosen by popular vote, legislative

appointment, or a combination of both four weeks before the election.

According

to Article Two of the U.S. Constitution, the states appointed a number

of presidential electors equal to the “number of Senators and

Representatives to which the state may be entitled in Congress.” Each

elector voted for two people, at least one of whom did not live in their

state. The individual receiving the greatest number of votes was

elected president, and the next-in-line, vice president. (In 1804, this

practice was changed by the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, which

ordered separate ballots for the office of president and vice

president.)

New York, though it was to be the seat of the new United

States government, failed to choose its eight presidential electors in

time for the vote on February 4, 1789. Two electors each from Virginia

and Maryland were delayed by weather and did not vote. In addition,

North Carolina and Rhode Island, which would have had seven and three

electors respectively, had not ratified the Constitution and so could

not vote.

That the remaining 69 unanimously chose Washington to lead

the new U.S. government was a surprise to no one. As commander-in-chief

during the Revolutionary War, he had led his inexperienced and poorly

equipped army of civilian soldiers to victory over one of the world’s

great powers. After the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781,

Washington rejected with abhorrence a suggestion by one of his officers

that he use his preeminence to assume a military dictatorship. He would

not subvert the very principles for which so many Americans had fought

and died, he replied, and soon after, he surrendered his military

commission to the Continental Congress and retired to his Mount Vernon

estate in Virginia.

When the Articles of Confederation proved

ineffectual, and the fledging republic teetered on the verge of

collapse, Washington again answered his country’s call and traveled to

Philadelphia in 1787 to preside over the Constitutional Convention.

Although he favored the creation of a strong central government, as

president of the convention he maintained impartiality in the public

debates. Outside the convention hall, however, he made his views known,

and his weight of character did much to bring the proceedings to a

close. The drafters created the office of president with him in mind,

and on September 17, 1787, the document was signed.

The next day,

Washington started for home, hoping that, his duty to his country again

served, he could live out the rest of his days in privacy. However, a

crisis soon arose when the Constitution fell short of its necessary

ratification by nine states. Washington threw himself into the

ratification debate, and a compromise agreement was made in which the

remaining states would ratify the document in exchange for passage of

the constitutional amendments that would become the Bill of Rights.

Government

by the United States began on March 4, 1789. In April, Congress sent

word to George Washington that he had unanimously won the presidency. He

borrowed money to pay off his debts in Virginia and traveled to New

York.

On April 30, he came across the Hudson River in a specially

built and decorated barge. The inaugural ceremony was performed on the

balcony of Federal Hall on Wall Street, and a large crowed cheered after

he took the oath of office. The president then retired indoors to read

Congress his inaugural address, a quiet speech in which he spoke of “the

experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.” The evening

celebration was opened and closed by 13 skyrockets and 13 cannons.

As

president, Washington sought to unite the nation and protect the

interests of the new republic at home and abroad. Of his presidency, he

said, “I walk on untrodden ground. There is scarcely any part of my

conduct which may not hereafter be drawn in precedent.” He successfully

implemented executive authority, making good use of brilliant

politicians such as Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson in his

Cabinet, and quieted fears of presidential tyranny. In 1792, he was

unanimously reelected but four years later refused a third term.

In

1797, he finally began his long-awaited retirement at Mount Vernon. He

died on December 14, 1799. His friend Henry Lee provided a famous eulogy

for the father of the United States: “First in war, first in peace, and

first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

John Adams

On February 4, 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama, delegates from South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana convene to establish the Confederate States of America.

As early as 1858, the ongoing conflict between the North and the South over the issue of slavery led Southern leadership to discuss a unified separation from the United States. By 1860, the majority of the slave states were publicly threatening secession if the Republicans, the anti-slavery party, won the presidency. Following Republican Abraham Lincoln’s victory over the divided Democratic Party in November 1860, South Carolina immediately initiated secession proceedings. On December 20, its legislature passed the “Ordinance of Secession,” which declared that “the Union now subsisting between South Carolina and other states, under the name of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved.” After the declaration, South Carolina set about seizing forts, arsenals, and other strategic locations within the state. Within six weeks, five more Southern states had followed South Carolina’s lead.

In February 1861, representatives from the six seceded states met in Montgomery, Alabama, to formally establish a unified government, which they named the Confederate States of America. On February 9, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was elected the Confederacy’s first president.

By the time Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1861, Texas had joined the Confederacy, and federal troops held only Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Fort Pickens off the Florida coast, and a handful of minor outposts in the South. On April 12, 1861, the American Civil War began when Confederate shore batteries under General P.G.T. Beauregard opened fire on Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Bay. Within two months, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee had all joined the embattled Confederacy.

Lithograph shows a crowd gathered in front of the capitol building in Montgomery, AL at the time of the announcement of Jefferson Davis as the first President of the Confederate States of America, c. 1888. Also shown with Davis are Stephens; Wm. L. Yancey, Leader of the Secession Party, and Howell Cobb, president of the Senate.

State House at Montgomery AL

On February 4, 1915, a full two years before Germany’s aggressive naval policy would draw the United States into the war against them, Kaiser Wilhelm announces an important step in the development of that policy, proclaiming the North Sea a war zone, in which all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, were liable to be sunk without warning.

In widening the boundaries of naval warfare, Germany was retaliating against the Allies for the British-imposed blockade of Germany in the North Sea, an important part of Britain’s war strategy aimed at strangling its enemy economically. By war’s end, according to official British counts, the so-called hunger blockade would take some 770,000 German lives.

The German navy, despite its attempts to build itself up in the pre-war years, was far inferior in strength to the peerless British Royal Navy. After resounding defeats of its battle cruisers, such as that suffered in the Falkland Islands in December 1914, Germany began to look to its dangerous U-boat submarines as its best hope at sea. Hermann Bauer, the leader of the German submarine service, had suggested in October 1914 that the U-boats could be used to attack commerce ships and raid their cargoes, thus scaring off imports to Britain, including those from neutral countries. Early the following month, Britain declared the North Sea a military area, warning neutral countries that areas would be mined and that all ships must first put into British ports, where they would be searched for possible supplies bound for Germany, stripped of these, and escorted through the British minefields. With this intensification of the blockade, Bauer’s idea gained greater support within Germany as the only appropriate response to Britain’s actions.

Though German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and the German Foreign Ministry worried about angering neutral countries, pressure from naval leaders and anger in the German press about the British blockade convinced them to go through with the declaration. On February 4, 1915, Kaiser Wilhelm announced Germany’s intention to sink any and all ships sailing under the flags of Britain, Russia or France found within British waters. The Kaiser warned neutral countries that neither crews nor passengers were safe while traveling within the designated war zone around the British Isles. If neutral ships chose to enter British waters after February 18, when the policy went into effect, they would be doing so at their own risk.

The U.S. government immediately and strongly protested the war-zone designation, warning Germany that it would take any steps it might be necessary to take in order to protect American lives and property. Subsequently, a rift opened between Germany’s politicians, who didn’t want to provoke America’s anger, and its navy, which was determined to use its deadly U-boats to the greatest possible advantage.

After a German U-boat sank the British passenger ship Lusitania on May 7, 1915, killing over 1,000 people, including 128 Americans, pressure from the U.S. prompted the German government to greatly constrain the operation of submarines; U-boat warfare was completely suspended that September. Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed on February 1, 1917, prompting the U.S., two days later, to break diplomatic relations with Germany.

Kaiser Wilhelm

This poster was printed as a warning and as a point of braggadocio marking all the ships sunk by German submarines in the North Sea.

On February 4, 1962, the first U.S. helicopter is shot down in Vietnam. It was one of 15 helicopters ferrying South Vietnamese Army troops into battle near the village of Hong My in the Mekong Delta.

The first U.S. helicopter unit had arrived in South Vietnam aboard the ferry carrier USNS Core on December 11, 1961. This contingent included 33 Vertol H-21C Shawnee helicopters and 400 air and ground crewmen to operate and maintain them. Their assignment was to airlift South Vietnamese Army troops into combat.

On February 4, 1826, The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper is published. One of the earliest distinctive American novels, the book is the second of the five-novel series called the “Leatherstocking Tales.”

Cooper was born in 1789 in New Jersey and moved the following year to the frontier in upstate New York, where his father founded frontier-town Coopersville. Cooper attended Yale but joined the Navy after he was expelled for a prank. When Cooper was about 20, his father died, and he became financially independent. Having drifted for a decade, Cooper began writing a novel after his wife challenged him to write something better than he was reading at the moment. His first novel, Precaution, modeled on Jane Austen, was not successful, but his second, The Spy, influenced by the popular writings of Sir Walter Scott, became a bestseller, making Cooper the first major American novelist. The story was set during the American Revolution and featured George Washington as a character.

He continued to write about the American frontier in his third book, The Pioneer, which featured backcountry scout Natty Bumppo, known in this book as “Leather-stocking.” The character, representing goodness, purity, and simplicity, became tremendously popular, and reappeared, by popular demand, in five more novels, known collectively as the “Leather-stocking Tales.” The second book in the series, The Last of the Mohicans, is still widely read today. The five books span Bumppo’s life, from coming of age through approaching death.

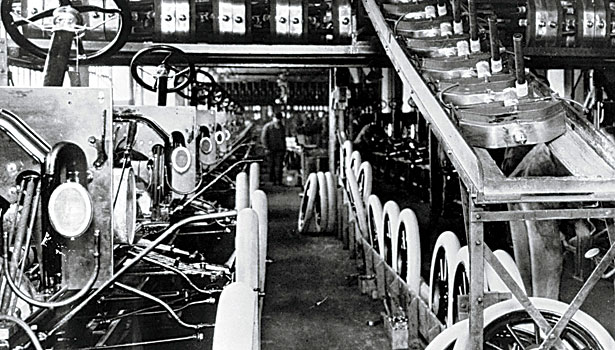

On February 4, 1922, the Ford Motor Company acquires the failing luxury automaker Lincoln Motor Company for $8 million.

The acquisition came at a time when Ford, founded in 1903, was losing market share to its competitor General Motors, which offered a range of automobiles while Ford continued to focus on its utilitarian Model T. Although the Model T, which first went into production in 1908, had become the world’s best-selling car and revolutionized the auto industry, it had undergone few major changes since its debut, and from 1914 to 1925 it was only available in one color: black. In May 1927, lack of demand for the Model T forced Ford to shut down the assembly lines on the iconic vehicle. Later that year, the company introduced the more comfortable and stylish Model A, a car whose sleeker look resembled that of a Lincoln automobile. In fact, the Model A was nicknamed “the baby Lincoln.”

Henry Leland, a founder of the Cadillac auto brand, established the Lincoln Motor Company in 1917; he reportedly named the new venture after his hero, President Abraham Lincoln. Facing financial difficulties, Lincoln was purchased by Ford in 1922. Henry Ford’s son, Edsel (1893-1943), was instrumental in convincing his father to buy Lincoln and played a significant role in its development as Ford’s first luxury division. Edsel Ford had succeeded his father as company president in January 1919, after the elder Ford resigned following a disagreement with a group of stockholders. However, father and son soon managed to purchase the stock of these minority investors and regain control of the company. One of Edsel Ford’s major contributions as president of Ford was the styling of cars, which he believed could be good-looking as well as functional. His push for style upgrades to the Model T eventually helped to convince his father to drop his famous rule: “You can have any color, as long as it’s black.” (The Model A, successor to the Model T, was available in a variety of colors from the start.)

In the 1930s, Ford’s Lincoln division introduced its popular Zephyr model, which was inspired by the Burlington Zephyr, a streamlined, diesel-powered express train that debuted amid great fanfare in 1934 and featured an engine built by General Motors. The Lincoln Continental, which architect Frank Lloyd Wright reportedly described as “the most beautiful car ever made,” launched in 1939 and was a flagship model for decades. President John Kennedy was riding in a 1961 Lincoln Continental when he was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, in 1963. Other leading Lincoln models over the years have included the Town Car, a full-size luxury sedan released in the 1980s (although Henry Ford had a custom-built vehicle called a Town Car in the 1920s), and the Navigator, a full-size luxury sport utility vehicle that launched in the late 1990s.

Henry Ford (left rear) stands beside Henry Leland, the owner of Lincoln Motor Company. They look over the next generation as they sign the papers as Ford purchases Lincoln. Edsel Ford is seated in front of his father and William Leland is seated in front of his father.