On This Date In History

On January 1, 1959, facing a popular revolution spearheaded by Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement, Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista flees the island nation. Amid celebration and chaos in the Cuban capitol of Havana, the U.S. debated how best to deal with the radical Castro and the ominous rumblings of anti-Americanism in Cuba.

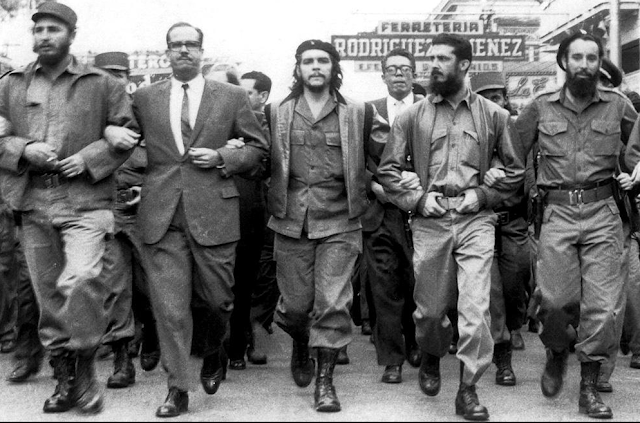

The U.S. government had supported Batista, a former soldier and Cuban dictator from 1933 to 1944, who seized power for a second time in a 1952 coup. After Castro and a group of followers, including the South American revolutionary Che Guevara (1928-1967), landed in Cuba to unseat the dictator in December 1956, the U.S. continued to back Batista. Suspicious of what they believed to be Castro’s leftist ideology and worried that his ultimate goals might include attacks on the U.S.’s significant investments and property in Cuba, American officials were nearly unanimous in opposing his revolutionary movement.

Cuban support for Castro’s revolution, however, grew in the late 1950s, partially due to his charisma and nationalistic rhetoric, but also because of increasingly rampant corruption, greed, brutality and inefficiency within the Batista government. This reality forced the U.S. to slowly withdraw its support from Batista and begin a search in Cuba for an alternative to both the dictator and Castro; these efforts failed.

On January 1, 1959, Batista and a number of his supporters fled Cuba for the Dominican Republic. Tens of thousands of Cubans (and thousands of Cuban Americans in the U.S.) celebrated the end of the dictator’s regime. Castro’s supporters moved quickly to establish their power. Judge Manuel Urrutia was named as provisional president. Castro and his band of guerrilla fighters triumphantly entered Havana on January 7.

The U.S. attitude toward the new revolutionary government soon changed from cautiously suspicious to downright hostile. After Castro nationalized American-owned property, allied himself with the Communist Party and grew friendlier with the Soviet Union, America’s Cold War enemy, the U.S severed diplomatic and economic ties with Cuba and enacted a trade and travel embargo that remains in effect, although some restriction were loosened under the Obama administration. In April 1961, the U.S. launched the Bay of Pigs invasion, an unsuccessful attempt to remove Castro from power. Subsequent covert operations to overthrow Castro, born August 13, 1926, failed and he went on to become one of the world’s longest-ruling heads of state. Fulgencio Batista died in Spain at age 72 on August 6, 1973. In late July 2006, an unwell Fidel Castro temporarily ceded power to his younger brother Raul. Fidel Castro officially stepped down in February 2008; he died on November 25, 2016.

Fidel Castro (Far Left) - Che Guevara (Center) - 1959

On January 1, 46 B.C., New Year’s Day is celebrated on January 1 for the first time in history as the Julian calendar takes effect.

Soon after becoming Roman dictator, Julius Caesar decided that the traditional Roman calendar was in dire need of reform. Introduced around the seventh century B.C., the Roman calendar attempted to follow the lunar cycle but frequently fell out of phase with the seasons and had to be corrected. In addition, the pontifices, the Roman body charged with overseeing the calendar, often abused its authority by adding days to extend political terms or interfere with elections.

In designing his new calendar, Caesar enlisted the aid of Sosigenes, an Alexandrian astronomer, who advised him to do away with the lunar cycle entirely and follow the solar year, as did the Egyptians. The year was calculated to be 365 and 1/4 days, and Caesar added 67 days to 46 B.C., making 45 B.C. begin on January 1, rather than in March. He also decreed that every four years a day be added to February, thus theoretically keeping his calendar from falling out of step. Shortly after Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C., Mark Anthony changed the name of the month Quintilis to Julius (July) to honor him. Later, the month of Sextilis was renamed Augustus (August) after his successor.

Celebration of New Year’s Day in January fell out of practice during the Middle Ages, and even those who strictly adhered to the Julian calendar did not observe the New Year exactly on January 1. The reason for the latter was that Caesar and Sosigenes failed to calculate the correct value for the solar year as 365.242199 days, not 365.25 days. Thus, an 11-minute-a-year error added seven days by the year 1000, and 10 days by the mid-15th century.

The Church became aware of this problem, and in the 1570s Pope Gregory XIII commissioned Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius to come up with a new calendar. In 1582, the Gregorian calendar was implemented, omitting 10 days for that year and establishing the new rule that only one of every four centennial years should be a leap year. Since then, people around the world have gathered en masse on January 1 to celebrate the precise arrival of the New Year.

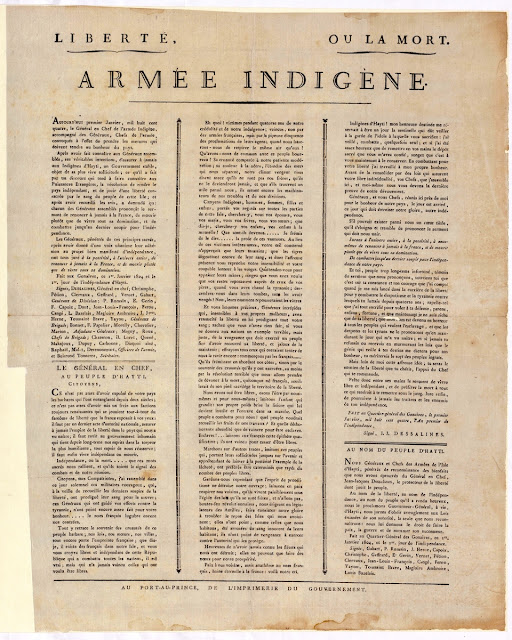

On January 1, 1803, two months after his defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte’s colonial forces, Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaims the independence of Saint-Domingue, renaming it Haiti after its original Arawak name.

In 1791, a slave revolt erupted on the French colony, and Toussaint-Louverture, a former slave, took control of the rebels. Gifted with natural military genius, Toussaint organized an effective guerrilla war against the island’s colonial population. He found able generals in two other former slaves, Dessalines and Henri Christophe, and in 1795 he made peace with revolutionary France following its abolishment of slavery. Toussaint became governor-general of the colony and in 1801 conquered the Spanish portion of island, freeing the slaves there.

In January 1802, an invasion force ordered by Napoleon landed on Saint-Domingue, and after several months of furious fighting, Toussaint agreed to a cease-fire. He retired to his plantation but in 1803 was arrested and taken to a dungeon in the French Alps, where he was tortured and died in April.

Soon after Toussaint’s arrest, Napoleon announced his intention to reintroduce slavery on Haiti, and Dessalines led a new revolt against French rule. With the aid of the British, the rebels scored a major victory against the French force there, and on November 9, 1803, colonial authorities surrendered. In 1804, General Dessalines assumed dictatorial power, and Haiti became the second independent nation in the Americas. Later that year, Dessalines proclaimed himself Emperor Jacques I. He was killed putting down a revolt two years later.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln signs the Emancipation Proclamation. Attempting to stitch together a nation mired in a bloody civil war, Abraham Lincoln made a last-ditch, but carefully calculated, decision regarding the institution of slavery in America.

By the end of 1862, things were not looking good for the Union. The Confederate Army had overcome Union troops in significant battles and Britain and France were set to officially recognize the Confederacy as a separate nation. In an August 1862 letter to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, Lincoln confessed “my paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” Lincoln hoped that declaring a national policy of emancipation would stimulate a rush of the South’s enslaved people into the ranks of the Union army, thus depleting the Confederacy’s labor force, on which the southern states depended to wage war against the North.

Lincoln waited to unveil the proclamation until he could do so on the heels of a Union military success. On September 22, 1862, after the battle at Antietam, he issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation declaring all enslaved people free in the rebellious states as of January 1, 1863. Lincoln and his advisors limited the proclamation’s language to slavery in states outside of federal control as of 1862, failing to address the contentious issue of slavery within the nation’s border states. In his attempt to appease all parties, Lincoln left many loopholes open that civil rights advocates would be forced to tackle in the future.

Republican abolitionists in the North rejoiced that Lincoln had finally thrown his full weight behind the cause for which they had elected him. Though enslaved people in the south failed to rebel en masse with the signing of the proclamation, they slowly began to liberate themselves as Union armies marched into Confederate territory. Toward the end of the war, enslaved people left their former masters in droves. They fought and grew crops for the Union Army, performed other military jobs and worked in the North’s mills. Though the proclamation was not greeted with joy by all northerners, particularly northern white workers and troops fearful of job competition from an influx of freed slaves, it had the distinct benefit of convincing Britain and France to steer clear of official diplomatic relations with the Confederacy.

Though the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation signified Lincoln’s growing resolve to preserve the Union at all costs, he still rejoiced in the ethical correctness of his decision. Lincoln admitted on that New Year’s Day in 1863 that he never “felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper.” Although he waffled on the subject of slavery in the early years of his presidency, he would thereafter be remembered as “The Great Emancipator.” To Confederate sympathizers, however, Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation reinforced their image of him as a hated despot and ultimately inspired his assassination by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865.

On January 1, 1946, an American soldier accepts the surrender of about 20 Japanese soldiers who only discovered that the war was over by reading it in the newspaper.

On the island of Corregidor, located at the mouth of Manila Bay, a lone soldier on detail for the American Graves Registration was busy recording the makeshift graves of American soldiers who had lost their lives fighting the Japanese. He was interrupted when approximately 20 Japanese soldiers approached him waving a white flag. They had been living in an underground tunnel built during the war and learned that their country had already surrendered when one of them ventured out in search of water and found a newspaper announcing Japan’s defeat.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_holdout

On January 1, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill issue a declaration, signed by representatives of 26 countries, called the “United Nations.” The signatories of the declaration vowed to create an international postwar peacekeeping organization.

On December 22, 1941, Churchill arrived in Washington, D.C., for the Arcadia Conference, a discussion with President Roosevelt about a unified Anglo-American war strategy and a future peace. The attack on Pearl Harbor meant that the U.S. was involved in the war, and it was important for Great Britain and America to create and project a unified front against Axis powers. Toward that end, Churchill and Roosevelt created a combined general staff to coordinate military strategy against both Germany and Japan and to draft a plan for a future joint invasion of the Continent.

Among the most far-reaching achievements of the Arcadia Conference was the United Nations agreement. Led by the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, the signatories agreed to use all available resources to defeat the Axis powers. It was agreed that no single country would sue for a separate peace with Germany, Italy, or Japan-they would act in concert. Perhaps most important, the signatories promised to pursue the creation of a future international peacekeeping organization dedicated to ensuring “life, liberty, independence, and religious freedom, and to preserve the rights of man and justice.”

Representatives of 26 Allied nations fighting against the Axis Powers met in Washington, D.C., to pledge their support for the Atlantic Charter by signing the Declaration by United Nations on January 1, 1942. The document contained the first official use of the term "United Nations", which was suggested by U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (seated, second from left).

No comments:

Post a Comment