On This Date In History

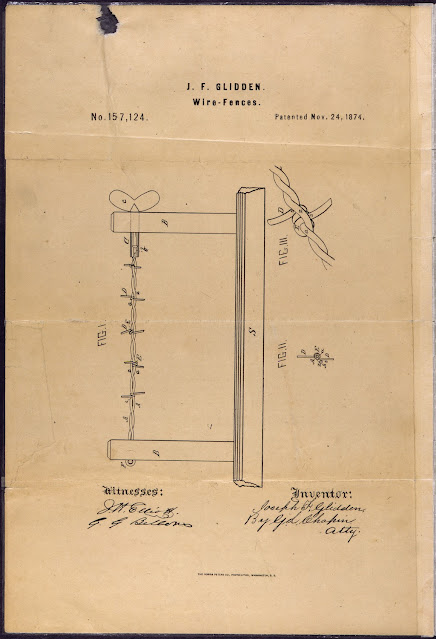

On October 27, 1873, a De Kalb, Illinois, farmer named Joseph Glidden submits an application to the U.S. Patent Office for his clever new design for a fencing wire with sharp barbs, an invention that will forever change the face of the American West.

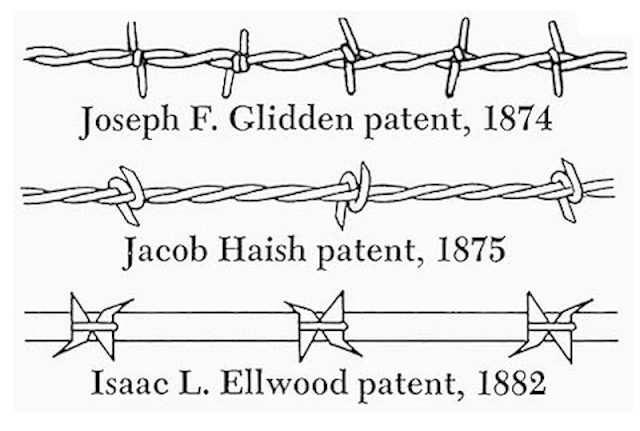

Glidden’s was by no means the first barbed wire; he only came up with his design after seeing an exhibit of Henry Rose’s single-stranded barbed wire at the De Kalb county fair. But Glidden’s design significantly improved on Rose’s by using two strands of wire twisted together to hold the barbed spur wires firmly in place. Glidden’s wire also soon proved to be well suited to mass production techniques, and by 1880 more than 80 million pounds of inexpensive Glidden-style barbed wire was sold, making it the most popular wire in the nation. Prairie and plains farmers quickly discovered that Glidden’s wire was the cheapest, strongest, and most durable way to fence their property. As one fan wrote, “it takes no room, exhausts no soil, shades no vegetation, is proof against high winds, makes no snowdrifts, and is both durable and cheap.”

The effect of this simple invention on the life in the Great Plains was huge. Since the plains were largely treeless, a farmer who wanted to construct a fence had little choice but to buy expensive and bulky wooden rails shipped by train and wagon from distant forests. Without the alternative offered by cheap and portable barbed wire, few farmers would have attempted to homestead on the Great Plains, since they could not have afforded to protect their farms from grazing herds of cattle and sheep. Barbed wire also brought a speedy end to the era of the open-range cattle industry. Within the course of just a few years, many ranchers discovered that thousands of small homesteaders were fencing over the open range where their cattle had once freely roamed, and that the old technique of driving cattle over miles of unfenced land to railheads in Dodge City or Abilene was no longer possible.

On October 27, 1775, King George III speaks before both houses of the British Parliament to discuss growing concern about the rebellion in America, which he viewed as a traitorous action against himself and Great Britain. He began his speech by reading a “Proclamation of Rebellion” and urged Parliament to move quickly to end the revolt and bring order to the colonies.

The king spoke of his belief that “many of these unhappy people may still retain their loyalty, and may be too wise not to see the fatal consequence of this usurpation, and wish to resist it, yet the torrent of violence has been strong enough to compel their acquiescence, till a sufficient force shall appear to support them.” With these words, the king gave Parliament his consent to dispatch troops to use against his own subjects, a notion that his colonists believed impossible.

Just as the Continental Congress expressed its desire to remain loyal to the British crown in the Olive Branch Petition, delivered to the monarch on September 1, so George III insisted he had “acted with the same temper; anxious to prevent, if it had been possible, the effusion of the blood of my subjects; and the calamities which are inseparable from a state of war; still hoping that my people in America would have discerned the traitorous views of their leaders, and have been convinced, that to be a subject of Great Britain, with all its consequences, is to be the freest member of any civil society in the known world.” King George went on to scoff at what he called the colonists’ “strongest protestations of loyalty to me,” believing them disingenuous, “whilst they were preparing for a general revolt.”

Unfortunately for George III, Thomas Paine’s anti-monarchical argument in the pamphlet, Common Sense, published in January 1776, proved persuasive to many American colonists. The two sides had reached a final political impasse and the bloody War for Independence soon followed.

On October 27, 1962, complicated and tension-filled negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union finally result in a plan to end the two-week-old Cuban Missile Crisis. A frightening period in which nuclear holocaust seemed imminent began to come to an end.

Since President John F. Kennedy’s October 22 address warning the Soviets to cease their reckless program to put nuclear weapons in Cuba and announcing a naval “quarantine” against additional weapons shipments into Cuba, the world held its breath waiting to see whether the two superpowers would come to blows. U.S. armed forces went on alert and the Strategic Air Command went to a Stage 4 alert (one step away from nuclear attack). On October 24, millions waited to see whether Soviet ships bound for Cuba carrying additional missiles would try to break the U.S. naval blockade around the island. At the last minute, the vessels turned around and returned to the Soviet Union.

On October 26, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev responded to the quarantine by sending a long and rather disjointed letter to Kennedy offering a deal: Soviet ships bound for Cuba would “not carry any kind of armaments” if the United States vowed never to invade Cuba. He pleaded, “let us show good sense,” and appealed to Kennedy to “weigh well what the aggressive, piratical actions, which you have declared the U.S.A. intends to carry out in international waters, would lead to.”

He followed this with another letter the next day offering to remove the missiles from Cuba if the United States would remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey. Kennedy and his officials debated the proper U.S. response to these offers. Attorney General Robert Kennedy ultimately devised an acceptable plan: take up Khrushchev’s first offer and ignore the second letter.

Although the United States had been considering the removal of the missiles from Turkey for some time, agreeing to the Soviet demand for their removal might give the appearance of weakness. Nevertheless, behind the scenes, Russian diplomats were informed that the missiles in Turkey would be removed after the Soviet missiles in Cuba were taken away. This information was accompanied by a threat: If the Cuban missiles were not removed in two days, the United States would resort to military action. It was now Khrushchev’s turn to consider an offer to end the standoff.

No comments:

Post a Comment