On This Date In History

On October 20, 1944, after advancing island by island across the Pacific Ocean, U.S. General Douglas MacArthur wades ashore onto the Philippine island of Leyte, fulfilling his promise to return to the area he was forced to flee in 1942.

The son of an American Civil War hero, MacArthur served as chief U.S. military adviser to the Philippines before World War II. The day after Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, Japan launched its invasion of the Philippines. After struggling against great odds to save his adopted home from Japanese conquest, MacArthur was forced to abandon the Philippine island fortress of Corregidor under orders from President Franklin Roosevelt in March 1942. Left behind at Corregidor and on the Bataan Peninsula were 90,000 American and Filipino troops, who, lacking food, supplies, and support, would soon succumb to the Japanese offensive.

After leaving Corregidor, MacArthur and his family traveled by boat 560 miles to the Philippine island of Mindanao, braving mines, rough seas, and the Japanese navy. At the end of the hair-raising 35-hour journey, MacArthur told the boat commander, John D. Bulkeley, “You’ve taken me out of the jaws of death, and I won’t forget it.” On March 17, the general and his family boarded a B-17 Flying Fortress for northern Australia. He then took another aircraft and a long train ride down to Melbourne. During this journey, he was informed that there were far fewer Allied troops in Australia than he had hoped. Relief of his forces trapped in the Philippines would not be forthcoming. Deeply disappointed, he issued a statement to the press in which he promised his men and the people of the Philippines, “I shall return.” The promise would become his mantra during the next two and a half years, and he would repeat it often in public appearances.

For his valiant defense of the Philippines, MacArthur was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and celebrated as “America’s First Soldier.” Put in command of Allied forces in the Southwestern Pacific, his first duty was conducting the defense of Australia. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, Bataan fell in April, and the 70,000 American and Filipino soldiers captured there were forced to undertake a death march in which at least 7,000 perished. Then, in May, Corregidor surrendered, and 15,000 more Americans and Filipinos were captured. The Philippines were lost, and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff had no immediate plans for their liberation.

After the U.S. victory at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, most Allied resources in the Pacific went to U.S. Admiral Chester Nimitz, who as commander of the Pacific Fleet planned a more direct route to Japan than via the Philippines. Undaunted, MacArthur launched a major offensive in New Guinea, winning a string of victories with his limited forces. By September 1944, he was poised to launch an invasion of the Philippines, but he needed the support of Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet. After a period of indecision about whether to invade the Philippines or Formosa, the Joint Chiefs put their support behind MacArthur’s plan, which logistically could be carried out sooner than a Formosa invasion.

On October 20, 1944, a few hours after his troops landed, MacArthur waded ashore onto the Philippine island of Leyte. That day, he made a radio broadcast in which he declared, “People of the Philippines, I have returned!” In January 1945, his forces invaded the main Philippine island of Luzon. In February, Japanese forces at Bataan were cut off, and Corregidor was captured. Manila, the Philippine capital, fell in March, and in June MacArthur announced his offensive operations on Luzon to be at an end; although scattered Japanese resistance continued until the end of the war, in August. Only one-third of the men MacArthur left behind in March 1942 survived to see his return. “I’m a little late,” he told them, “but we finally came.”

On October 20, 1803, the U.S. Senate approves a treaty with France providing for the purchase of the territory of Louisiana, which would double the size of the United States.

At the end of 18th century, the Spanish technically owned Louisiana, the huge region west of the Mississippi that had once been claimed by France and named for its monarch, King Louis XIV. Despite Spanish ownership, American settlers in search of new land were already threatening to overrun the territory by the early 19th century. Recognizing it could not effectively maintain control of the region, Spain ceded Louisiana back to France in 1801, sparking intense anxieties in Washington, D.C. Under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte, France had become the most powerful nation in Europe, and unlike Spain, it had the military power and the ambition to establish a strong colony in Louisiana and keep out the Americans.

Realizing that it was essential that the U.S. at least maintain control of the mouth of the all-important Mississippi River, early in 1803 President Thomas Jefferson sent James Monroe to join the French foreign minister, Robert Livingston, in France to see if Napoleon might be persuaded to sell New Orleans and West Florida to the U.S. By that spring, the European situation had changed radically. Napoleon, who had previously envisioned creating a mighty new French empire in America, was now facing war with Great Britain. Rather than risk the strong possibility that Great Britain would quickly capture Louisiana and leave France with nothing, Napoleon decided to raise money for his war and simultaneously deny his enemy plum territory by offering to sell the entire territory to the U.S. for a mere $15 million. Flabbergasted, Monroe and Livingston decided that they couldn’t pass up such a golden opportunity, and they wisely overstepped the powers delegated to them and accepted Napoleon’s offer.

Despite his misgivings about the constitutionality of the purchase (the Constitution made no provision for the addition of territory by treaty), Jefferson finally agreed to send the treaty to the U.S. Senate for ratification, noting privately, “The less we say about constitutional difficulties the better.” Despite his concerns, the treaty was ratified and the Louisiana Purchase now ranks as the greatest achievement of Jefferson’s presidency.

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty, signed in Paris, April 30, 1803. (National Archives Identifier 7891099)

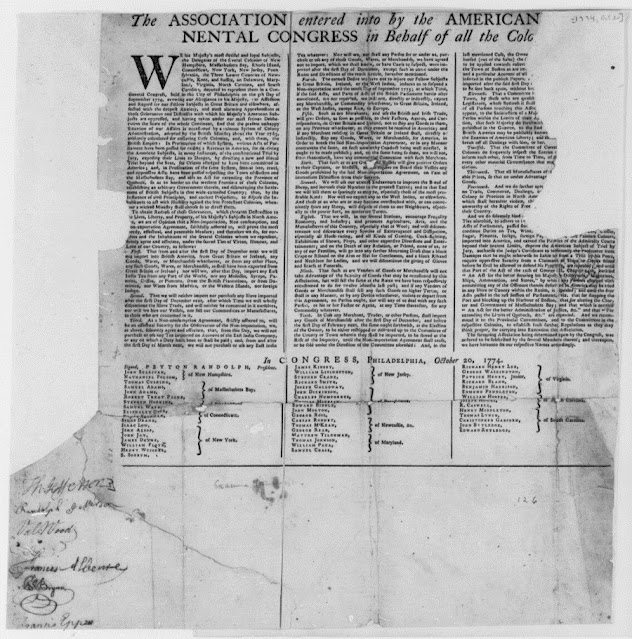

On October 20, 1774, the First Continental Congress creates the Continental Association, which calls for a complete ban on all trade between America and Great Britain of all goods, wares or merchandise.

The creation of the association was in response to the Coercive Acts, or “Intolerable Acts” as they were known to the colonists, which were established by the British government to restore order in Massachusetts following the Boston Tea Party.

The Intolerable Acts were a set of four acts: The first was the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston to all colonists until damages from the Boston Tea Party were paid. The second, the Massachusetts Government Act, gave the British government total control of town meetings, taking all decisions out of the hands of the colonists. The third, the Administration of Justice Act, made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in America and the fourth, the Quartering Act, required colonists to house and quarter British troops on demand, including in private homes as a last resort.

Outraged by the new laws mandated by the British Parliament, the Continental Association hoped that cutting off all trade with Great Britain would cause enough economic hardship there that the Intolerable Acts would be repealed. It was one of the first acts of Congress behind which every colony firmly stood.

Text of the Continental Association

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Continental_Association

On October 20, 1962, the White House press corps is told that President John F. Kennedy has a cold; in reality, he is holding secret meetings with advisors on the eve of ordering a blockade of Cuba.

Kennedy was in Seattle and scheduled to attend the Seattle Century 21 World’s Fair when his press secretary announced that he had contracted an “upper respiratory infection.” The president then flew back to Washington, where he supposedly went to bed to recover from his cold.

Four days earlier, Kennedy had seen photographic proof that the Soviets were building 40 ballistic missile sites on the island of Cuba, within striking distance of the United States. Kennedy’s supposed bed rest was actually a marathon secret session with advisors to decide upon a response to the Soviet action. The group believed that Kennedy had three choices: to negotiate with the Russians to remove the missiles; to bomb the missile sites in Cuba; or implement a naval blockade of the island. Kennedy chose to blockade Cuba, deciding to bomb the missile sites only if further action proved necessary.

The blockade began October 21 and, the next day, Kennedy delivered a public address alerting Americans to the situation and calling on Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to remove the missiles or face retaliation by the United States. Khrushchev responded by sending more ships, possibly carrying military cargo, toward Cuba and allowing construction at the sites to continue. Over the following six days, the Cuban Missile Crisis, as it is now known, brought the world to the brink of global nuclear war while the two leaders engaged in tense negotiations via telegram and letter.

By October 28, Kennedy and Khrushchev had reached a settlement and people on both sides of the conflict breathed a collective but wary sigh of relief. The Cuban missile sites were dismantled and, in return, Kennedy agreed to close U.S. missile sites in Turkey.

No comments:

Post a Comment