On This Date In History

On October 2, 1944, the Warsaw Uprising ends on October 2, 1944, with the surrender of the surviving Polish rebels to German forces.

Two months earlier, the approach of the Red Army to Warsaw prompted Polish resistance forces to launch a rebellion against the Nazi occupation. The rebels, who supported the democratic Polish government-in-exile in London, hoped to gain control of the city before the Soviets “liberated” it. The Poles feared that if they failed to take the city the Soviet conquerors would forcibly set up a pro-Soviet communist regime in Poland.

The poorly supplied Poles made early gains against the Germans, but Nazi leader Adolf Hitler sent reinforcements. In brutal street fighting, the Poles were gradually overcome by superior German weaponry. Meanwhile, the Red Army occupied a suburb of Warsaw but made no efforts to aid the Polish rebels. The Soviets also rejected a request by the British to use Soviet air bases to airlift supplies to the beleaguered Poles.

After 63 days, the Poles, out of arms, supplies, food, and water, were forced to surrender. In the aftermath, the Nazis deported much of Warsaw’s population and destroyed the city. With protestors in Warsaw out of the way, the Soviets faced little organized opposition in establishing a communist government in Poland.

On October 2, 1941, the Germans begin their surge to Moscow, led by the 1st Army Group and Gen. Fedor von Bock. Russian peasants in the path of Hitler’s army employ a “scorched-earth” policy.

Hitler’s forces had invaded the Soviet Union in June, and early on it had become one relentless push inside Russian territory. The first setback came in August, when the Red Army’s tanks drove the Germans back from the Yelnya salient. Hitler confided to General Bock at the time: “Had I known they had as many tanks as that, I’d have thought twice before invading.” But there was no turning back for Hitler, he believed he was destined to succeed where others had failed, and capture Moscow.

Although some German generals had warned Hitler against launching Operation Typhoon as the harsh Russian winter was just beginning, remembering the fate that befell Napoleon, who got bogged down in horrendous conditions, losing serious numbers of men and horses, Bock urged him on. This encouragement, coupled with the fact that the Germany army had taken the city of Kiev in late September, caused Hitler to declare, “The enemy is broken and will never be in a position to rise again.” So for 10 days, starting October 2, the 1st Army Group drove east, drawing closer to the Soviet capital each day. But the Russians also remembered Napoleon and began destroying everything as they fled their villages, fields, and farms. Harvested crops were burned, livestock were driven away, and buildings were blown up, leaving nothing of value behind to support exhausted troops. Hitler’s army inherited nothing but ruins.

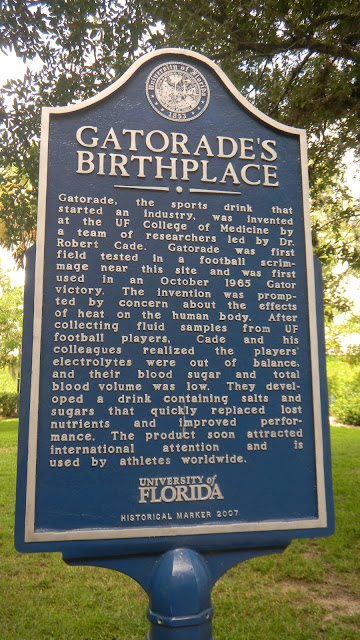

On October 2, 1965, a team of scientists invent Gatorade, a sports drink to quench thirst, in a University of Florida lab. The name "Gatorade" is derived from the nickname of the university's sports teams. Eventually, the drink becomes a phenomenon and makes its inventors wealthy.

Early in the summer of 1965, University of Florida assistant football coach Dewayne Douglas met a group of scientists on campus to determine why many of Florida's players were so negatively affected by heat. To replace bodily fluids lost during physical exertion, Dr. James Robert Cade and his team of researchers, doctors H. James Free, Dana Shires and Alex de Quesada, created the now-ubiquitous sports drink.

"They developed a drink that contained salts and sugars that could be absorbed more quickly," according to a University of Florida history of medicine, "and the basis for Gatorade was formed."

In its early days, Gatorade wasn't a hit with players. The drink reportedly tasted so awful that some athletes vomited after consuming it.

By 2015, however, royalties for the group that invented Gatorade, as well as some of their family members and friends, had eclipsed $1 billion.

On October 2, 1835, the growing tensions between Mexico and Texas erupt into violence when Mexican soldiers attempt to disarm the people of Gonzales, sparking the Texan war for independence.

Texas, or Tejas as the Mexicans called it, had technically been a part of the Spanish empire since the 17th century. However, even as late as the 1820s, there were only about 3,000 Spanish-Mexican settlers in Texas, and Mexico City’s hold on the territory was tenuous at best. After winning its own independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico welcomed large numbers of Anglo-American immigrants into Texas in the hopes they would become loyal Mexican citizens and keep the territory from falling into the hands of the United States. During the next decade men like Stephen Austin brought more than 25,000 people to Texas, most of them Americans. But while these emigrants legally became Mexican citizens, they continued to speak English, formed their own schools, and had closer trading ties to the United States than to Mexico.

In 1835, the president of Mexico, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, overthrew the constitution and appointed himself dictator. Recognizing that the “American” Texans were likely to use his rise to power as an excuse to secede, Santa Anna ordered the Mexican military to begin disarming the Texans whenever possible. This proved more difficult than expected, and on October 2, 1835, Mexican soldiers attempting to take a small cannon from the village of Gonzales encountered stiff resistance from a hastily assembled militia of Texans. After a brief fight, the Mexicans retreated and the Texans kept their cannon.

The determined Texans would continue to battle Santa Ana and his army for another year and a half before winning their independence and establishing the Republic of Texas.

No comments:

Post a Comment