On This Date In History

On September 3, 1783, the American Revolution officially comes to an end when representatives of the United States, Great Britain, Spain and France sign the Treaty of Paris. The signing signified America’s status as a free nation, as Britain formally recognized the independence of its 13 former American colonies, and the boundaries of the new republic were agreed upon: Florida north to the Great Lakes and the Atlantic coast west to the Mississippi River.

The events leading up to the treaty stretched back to April 1775, on a common green in Lexington, Massachusetts, when American colonists answered King George III’s refusal to grant them political and economic reform with armed revolution. On July 4, 1776, more than a year after the first volleys of the war were fired, the Second Continental Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence. Five difficult years later, in October 1781, British General Charles Lord Cornwallis surrendered to American and French forces at Yorktown, Virginia, bringing to an end the last major battle of the Revolution.

In September 1782, Benjamin Franklin, along with John Adams and John Jay, began official peace negotiations with the British. The Continental Congress had originally named a five-person committee, including Franklin, Adams and Jay, along with Thomas Jefferson and Henry Laurens, to handle the talks. However, both Jefferson and Laurens missed the sessions, Jefferson had travel delays and Laurens had been captured by the British and was being held in the Tower of London. The U.S. delegation, which was distrustful of the French, opted to negotiate separately with the British.

During the talks Franklin demanded that Britain hand over Canada to the United States. This did not come to pass, but America did gain enough new territory south of the Canadian border to double its size. The United States also successfully negotiated for important fishing rights in Canadian waters and agreed, among other things, not to prevent British creditors from attempting to recover debts owed to them. Two months later, the key details had been hammered out and on November 30, 1782, the United States and Britain signed the preliminary articles of the treaty. France signed its own preliminary peace agreement with Britain on January 20, 1783, and then in September of that year, the final treaty was signed by all three nations and Spain. The Treaty of Paris was ratified by the Continental Congress on January 14, 1784.

On September 3, 1777, the American flag is flown in battle for the first time, during a Revolutionary War skirmish at Cooch’s Bridge, Delaware. Patriot General William Maxwell ordered the stars and strips banner raised as a detachment of his infantry and cavalry met an advance guard of British and Hessian troops. The rebels were defeated and forced to retreat to General George Washington’s main force near Brandywine Creek in Pennsylvania.

Three months before, on June 14, the Continental Congress adopted a resolution stating that “the flag of the United States be thirteen alternate stripes red and white” and that “the Union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation.” The national flag, which became known as the “Stars and Stripes,” was based on the “Grand Union” flag, a banner carried by the Continental Army in 1776 that also consisted of 13 red and white stripes. According to legend, Philadelphia seamstress Betsy Ross designed the new canton for the Stars and Stripes, which consisted of a circle of 13 stars and a blue background, at the request of General George Washington. Historians have been unable to conclusively prove or disprove this legend.

With the entrance of new states into the United States after independence, new stripes and stars were added to represent new additions to the Union. In 1818, however, Congress enacted a law stipulating that the 13 original stripes be restored and that only stars be added to represent new states.

On June 14, 1877, the first Flag Day observance was held on the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the Stars and Stripes. As instructed by Congress, the U.S. flag was flown from all public buildings across the country. In the years after the first Flag Day, several states continued to observe the anniversary, and in 1949 Congress officially designated June 14 as Flag Day, a national day of observance.

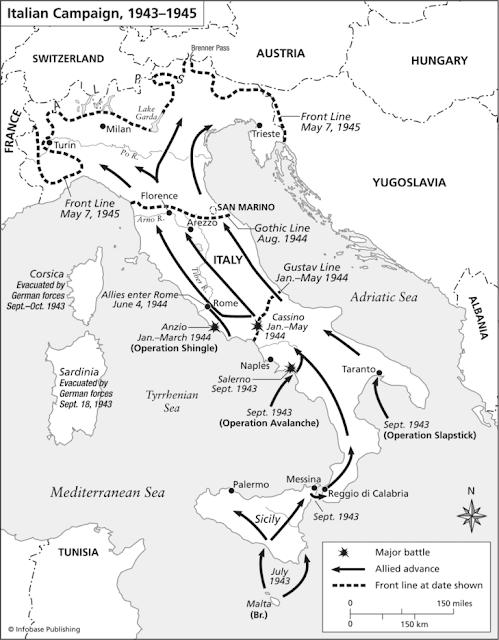

On September 3, 1943, the British 8th Army under Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery begins the Allied invasion of the Italian peninsula, crossing the Strait of Messina from Sicily and landing at Calabria, the “toe” of Italy. On the day of the landing, the Italian government secretly agreed to the Allies’ terms for surrender, but no public announcement was made until September 8.

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini envisioned building Fascist Italy into a new Roman Empire, but a string of military defeats in World War II effectively made his regime a puppet of its stronger Axis partner, Germany. By the spring of 1943, opposition groups in Italy were uniting to overthrow Mussolini and make peace with the Allies, but a strong German military presence in Italy threatened to resist any such action.

On July 10, 1943, the Allies began their invasion of Axis-controlled Europe with landings on the island of Sicily, off mainland Italy. Encountering little resistance from demoralized Sicilian troops, Montgomery’s 8th Army came ashore on the southeast part of the island, while the U.S. 7th Army, under General George S. Patton, landed on Sicily’s south coast. Within three days, 150,000 Allied troops were ashore. On August 17, Patton arrived in Messina before Montgomery, completing the Allied conquest of Sicily and winning the so-called Race to Messina.

In Rome, the Allied conquest of Sicily, a region of the kingdom of Italy since 1860, led to the collapse of Mussolini’s government. Early in the morning of July 25, he was forced to resign by the Fascist Grand Council and was arrested later that day. On July 26, Marshal Pietro Badoglio assumed control of the Italian government. The new government promptly entered into secret negotiations with the Allies, despite the presence of numerous German troops in Italy.

On September 3, Montgomery’s 8th Army began its invasion of the Italian mainland and the Italian government agreed to surrender to the Allies. By the terms of the agreement, the Italians would be treated with leniency if they aided the Allies in expelling the Germans from Italy. Later that month, Mussolini was rescued from a prison in the Abruzzo Mountains by German commandos and was installed as leader of a Nazi puppet state in northern Italy.

In October, the Badoglio government declared war on Germany, but the Allied advance up through Italy proved to be a slow and costly affair. Rome fell in June 1944, at which point a stalemate ensued as British and American forces threw most of their resources into the Normandy invasion. In April 1945, a new major offensive began, and on April 28 Mussolini was captured by Italian partisans and summarily executed. German forces in Italy surrendered on May 1, and six days later all of Germany surrendered.

On September 3, 1939, in response to Hitler’s invasion of Poland, Britain and France, both allies of the overrun nation declare war on Germany.

The first casualty of that declaration was not German, but the British ocean liner Athenia, which was sunk by a German U-30 submarine that had assumed the liner was armed and belligerent. There were more than 1,100 passengers on board, 112 of whom lost their lives. Of those, 28 were Americans, but President Roosevelt was unfazed by the tragedy, declaring that no one was to “thoughtlessly or falsely talk of America sending its armies to European fields.” The United States would remain neutral.

As for Britain’s response, it was initially no more than the dropping of anti-Nazi propaganda leaflets, 13 tons of them, over Germany. They would begin bombing German ships on September 4, suffering significant losses. They were also working under orders not to harm German civilians. The German military, of course, had no such restrictions. France would begin an offensive against Germany’s western border two weeks later. Their effort was weakened by a narrow 90-mile window leading to the German front, enclosed by the borders of Luxembourg and Belgium, both neutral countries. The Germans mined the passage, stalling the French offensive.

No comments:

Post a Comment