On This Date In History

On Sept 30, 1954, the USS Nautilus (USS 571), the world’s first nuclear submarine, is commissioned by the U.S. Navy.

The Nautilus was constructed under the direction of U.S. Navy Captain Hyman G. Rickover, a brilliant Russian-born engineer who joined the U.S. atomic program in 1946. In 1947, he was put in charge of the navy’s nuclear-propulsion program and began work on an atomic submarine. Regarded as a fanatic by his detractors, Rickover succeeded in developing and delivering the world’s first nuclear submarine years ahead of schedule. In 1952, the Nautilus‘ keel was laid by President Harry S. Truman, and on January 21, 1954, first lady Mamie Eisenhower broke a bottle of champagne across its bow as it was launched into the Thames River at Groton, Connecticut, from the Electric Boat Company. Commissioned on September 30, 1954, it first ran under nuclear power on the morning of January 17, 1955.

Much larger than the diesel-electric submarines that preceded it, the Nautilus stretched 319 feet and displaced 3,180 tons. It could remain submerged for almost unlimited periods because its atomic engine needed no air and only a very small quantity of nuclear fuel. The uranium-powered nuclear reactor produced steam that drove propulsion turbines, allowing the Nautilus to travel underwater at speeds in excess of 20 knots.

In its early years of service, the USS Nautilus broke numerous submarine travel records and in August 1958 accomplished the first voyage under the geographic North Pole. After a career spanning 25 years and almost 500,000 miles steamed, the Nautilus was decommissioned on March 3, 1980. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1982, the world’s first nuclear submarine went on exhibit in 1986 as the Historic Ship Nautilus at the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, Connecticut.

On September 30, 1822, Joseph Marion Hernández (Whig) becomes the first Hispanic to be elected to the United States Congress. Born a Spanish citizen, Hernández would die in Cuba, but in between he became the first non-white person to serve at the highest levels of any of three branches of the American federal government.

Hernández belonged to a St. Augustine family that came to Florida as indentured servants. Despite these humble beginnings, records show that his family eventually became wealthy enough to own property and several slaves, and that Hernández was educated both in both Georgia and in Cuba. Throughout the 1810s, the United States made a variety of efforts to take Florida from the Spanish, finally succeeding after Andrew Jackson led an army through the territory in the First Seminole War. What Hernández did during this time is unclear, but he was either very savvy or very lucky, he fought the Americans during the war and received substantial amounts of land from the Spanish government, but then pledged loyalty to the United States and was allowed to keep his three plantations when the territory changed hands in 1819. It was then that Hernández changed his name from José Mariano to Joseph Marion.

The newly-acquired Florida Territory was allowed to elect a delegate to congress, but that delegate did not have voting privileges. Florida's legislative council elected Hernández to represent the territory. During his brief tenure, he served for less than a year before losing his re-election bid, Hernández was instrumental in facilitating the transition from Spanish to American government in Florida. In addition to securing the property rights of many Floridians who remained after the annexation, he also advocated for roads and infrastructure to bind the new territory together and make it an attractive candidate for statehood.

He went on to fight in the Second Seminole War, helping his adopted nation drive the natives from its new territory. The war saw the loss of two of his plantations, however, as well the destruction of his political ambitions after he was involved in an incident in which an American contingent captured a number of Seminoles despite approaching them under a flag of truce. Hernández later served as Mayor of St. Augustine before retiring to Cuba, where he died in 1857.

On September 30, 1938, British and French prime ministers Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier sign the Munich Pact with Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. The agreement averted the outbreak of war but gave Czechoslovakia away to German conquest.

In the spring of 1938, Hitler began openly to support the demands of German-speakers living in the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia for closer ties with Germany. Hitler had recently annexed Austria into Germany, and the conquest of Czechoslovakia was the next step in his plan of creating a “greater Germany.” The Czechoslovak government hoped that Britain and France would come to its assistance in the event of German invasion, but British Prime Minister Chamberlain was intent on averting war. He made two trips to Germany in September and offered Hitler favorable agreements, but the Fuhrer kept upping his demands.

On September 22, Hitler demanded the immediate cession of the Sudetenland to Germany and the evacuation of the Czechoslovak population by the end of the month. The next day, Czechoslovakia ordered troop mobilization. War seemed imminent, and France began a partial mobilization on September 24. Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Daladier, unprepared for the outbreak of hostilities, traveled to Munich, where they gave in to Hitler’s demands on September 30.

Daladier abhorred the Munich Pact’s appeasement of the Nazis, but Chamberlain was elated and even stayed behind in Munich to sign a single-page document with Hitler that he believed assured the future of Anglo-German peace. Later that day, Chamberlain flew home to Britain, where he addressed a jubilant crowd in London and praised the Munich Pact for bringing “peace with honor” and “peace in our time.” The next day, Germany annexed the Sudetenland, and the Czechoslovak government chose submission over destruction by the German Wehrmacht. In March 1939, Hitler annexed the rest of Czechoslovakia, and the country ceased to exist.

On September 1, 1939, 53 German army divisions invaded Poland despite British and French threats to intervene on the nation’s behalf. Two days later, Chamberlain solemnly called for a British declaration of war against Germany, and World War II began. After eight months of ineffectual wartime leadership, Chamberlain was replaced as prime minister by Winston Churchill.

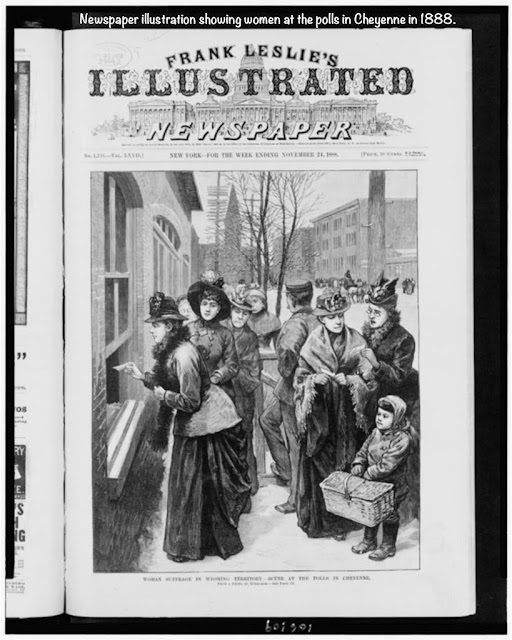

On September 30, 1889, the Wyoming state convention approves a constitution that includes a provision granting women the right to vote. Formally admitted into the union the following year, Wyoming thus became the first state in the history of the nation to allow its female citizens to vote.

That the isolated western state of Wyoming should be the first to accept women’s suffrage was a surprise. Leading suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were Easterners, and they assumed that their own more progressive home states would be among the first to respond to the campaign for women’s suffrage. Yet the people and politicians of the growing number of new Western states proved far more supportive than those in the East.

In 1848, the legislature in Washington Territory became the first to introduce a women’s suffrage bill. Though the Washington bill was narrowly defeated, similar legislation succeeded elsewhere, and Wyoming Territory was the first to give women the vote in 1869, quickly followed by Utah Territory (1870) and Washington Territory (1883). As with Wyoming, when these territories became states they preserved women’s suffrage.

By 1914, the contrast between East and West had become striking. All of the states west of the Rockies had women’s suffrage, while no state did east of the Rockies, except Kansas. Why the regional distinction? Some historians suggest western men may have been rewarding pioneer women for their critical role in settling the West. Others argue the West had a more egalitarian spirit, or that the scarcity of women in some western regions made men more appreciative of the women who were there while hoping the vote might attract more.

Whatever the reasons, while the Old West is usually thought of as a man’s world, a wild land that was “no place for a woman,” Westerners proved far more willing than other Americans to create states where women were welcomed as full and equal citizens.

Newspaper illustration showing women at the polls in Cheyenne in 1888.

On September 30, 1949, after 15 months and more than 250,000 flights, the Berlin Airlift officially comes to an end. The airlift was one of the greatest logistical feats in modern history and was one of the crucial events of the early Cold War.

In June 1948, the Soviet Union suddenly blocked all ground traffic into West Berlin, which was located entirely within the Russian zone of occupation in Germany. It was an obvious effort to force the United States, Great Britain, and France (the other occupying powers in Germany) to accept Soviet demands concerning the postwar fate of Germany. As a result of the Soviet blockade, the people of West Berlin were left without food, clothing, or medical supplies.

Some U.S. officials pushed for an aggressive response to the Soviet provocation, but cooler heads prevailed and a plan for an airlift of supplies to West Berlin was developed. It was a daunting task: supplying the daily wants and needs of so many civilians would require tons of food and other goods each and every day. On June 26, 1948, the Berlin Airlift began with U.S. pilots and planes carrying the lion’s share of the burden. During the next 15 months, 277,264 aircraft landed in West Berlin bringing over 2 million tons of supplies. On September 30, 1949, the last plane, an American C-54, landed in Berlin and unloaded over two tons of coal. Even though the Soviet blockade officially ended in May 1949, it took several more months for the West Berlin economy to recover and the necessary stockpiles of food, medicine, and fuel to be replenished.

The Berlin Airlift was a tremendous Cold War victory for the United States. Without firing a shot, the Americans foiled the Soviet plan to hold West Berlin hostage, while simultaneously demonstrating to the world the “Yankee ingenuity” for which their nation was famous. For the Soviets, the Berlin crisis was an unmitigated disaster. The United States, France, and Great Britain merely hardened their resolve on issues related to Germany, and the world came to see the Russians as international bullies, trying to starve innocent citizens.

No comments:

Post a Comment