On This Date In History

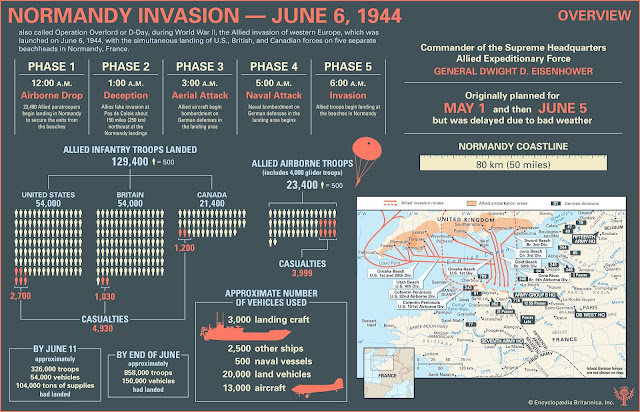

On June 6, 1944, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower gives the go-ahead for the largest amphibious military operation in history: Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of northern France, commonly known as D-Day.

By daybreak, 18,000 British and American parachutists were already on the ground. An additional 13,000 aircraft were mobilized to provide air cover and support for the invasion. At 6:30 a.m., American troops came ashore at Utah and Omaha beaches.

The British and Canadians overcame light opposition to capture Gold, Juno and Sword beaches; so did the Americans at Utah. The task was much tougher at Omaha beach, however, where the U.S. First Division battled high seas, mist, mines, burning vehicles, and German coastal batteries, including an elite infantry division, which spewed heavy fire. Many wounded Americans ultimately drowned in the high tide. British divisions, which landed at Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches, and Canadian troops, Juno, also met with heavy German fire.

But by day’s end, 155,000 Allied troops, Americans, British and Canadians, had successfully stormed Normandy’s beaches and were then able to push inland. Within three months, the northern part of France would be freed and the invasion force would be preparing to enter Germany, where they would meet up with Soviet forces moving in from the east.

Before the Allied assault, Hitler’s armies had been in control of most of mainland Europe and the Allies knew that a successful invasion of the continent was central to winning the war. Hitler knew this too, and was expecting an assault on northwestern Europe in the spring of 1944. He hoped to repel the Allies from the coast with a strong counterattack that would delay future invasion attempts, giving him time to throw the majority of his forces into defeating the Soviet Union in the east. Once that was accomplished, he believed an all-out victory would soon be his.

For their part, the Germans suffered from confusion in the ranks and the absence of celebrated commander Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who was away on leave. At first, Hitler, believing that the invasion was a feint designed to distract the Germans from a coming attack north of the Seine River, refused to release nearby divisions to join the counterattack and reinforcements had to be called from further afield, causing delays.

He also hesitated in calling for armored divisions to help in the defense. In addition, the Germans were hampered by effective Allied air support, which took out many key bridges and forced the Germans to take long detours, as well as efficient Allied naval support, which helped protect advancing Allied troops.

Though D-Day did not go off exactly as planned, as later claimed by British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, for example, the Allies were able to land only fractions of the supplies and vehicles they had intended in France, the invasion was a decided success. By the end of June, the Allies had 850,000 men and 150,000 vehicles in Normandy and were poised to continue their march across Europe.

What Does The “D” In D-Day Mean?

Time magazine reported on June 12 [1944] that “as far as the U.S. Army can determine, the first use of D for Day, H for Hour was in Field Order No. 8, of the First Army, A.E.F., issued on Sept. 20, 1918, which read, ‘The First Army will attack at H-Hour on D-Day with the object of forcing the evacuation of the St. Mihiel salient.’” (p. 491) In other words, the D in D-Day merely stands for Day. This coded designation was used for the day of any important invasion or military operation. For military planners (and later historians), the days before and after a D-Day were indicated using plus and minus signs: D-4 meant four days before a D-Day, while D+7 meant seven days after a D-Day.

Robert Hendrickson’s Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins

Many explanations have been given for the meaning of D-Day, June 6, 1944, the day the Allies invaded Normandy from England during World War II. The Army has said that it is “simply an alliteration, as in H-Hour.”

When someone wrote to General Eisenhower in 1964 asking for an explanation, his executive assistant Brigadier General Robert Schultz answered: “General Eisenhower asked me to respond to your letter. Be advised that any amphibious operation has a ‘departed date’; therefore the shortened term ‘D-Day’ is used.” (p.146)

Brigadier General Schultz reminds us that the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944 was not the only D-Day of World War II. Every amphibious assault, including those in the Pacific, in North Africa, and in Sicily and Italy, had its own D-Day.

On June 6, 1949, George Orwell's novel of a dystopian future, 1984, is published. The novel’s all-seeing leader, known as “Big Brother,” becomes a universal symbol for intrusive government and oppressive bureaucracy.

George Orwell was the nom de plume of Eric Blair, who was born in India. The son of a British civil servant, Orwell attended school in London and won a scholarship to the elite prep school Eton, where most students came from wealthy upper-class backgrounds, unlike Orwell. Rather than going to college like most of his classmates, Orwell joined the Indian Imperial Police and went to work in Burma in 1922. During his five years there, he developed a severe sense of class guilt; finally in 1927, he chose not to return to Burma while on holiday in England.

Orwell, choosing to immerse himself in the experiences of the urban poor, went to Paris, where he worked menial jobs, and later spent time in England as a tramp. He wrote Down and Out in Paris and London in 1933, based on his observation of the poorer classes, and in 1937 The Road to Wigan Pier, which documented the life of the unemployed in northern England. Meanwhile, he had published his first novel, Burmese Days, in 1934.

Orwell never committed himself to any specific political party. He went to Spain during the Spanish Civil War to fight on the side of the Republicans, but later fled as communism gained an upper hand in the struggle on the left. His barnyard fable, Animal Farm (1945), shows how the noble ideals of egalitarian economies can easily be distorted. The book brought him his first taste of critical and financial success. Orwell’s last novel, 1984, brought him lasting fame with its grim vision of a future where all citizens are watched constantly and language is twisted to aid in oppression.

No comments:

Post a Comment